To achieve a great leap, an entire generation must be sacrificed.

Liu Zhijun, Minister of Railways 2003-2011, People’s Republic of China

Edel Assanti is pleased to present Gordon Cheung’s fourth solo show with the gallery, Tears of Paradise. This exhibition is the latest in a series in which Cheung witnesses and interprets the emergence of China as a twenty first century global superpower, framing current events in the context of the Century of Humiliation and the Opium Wars.

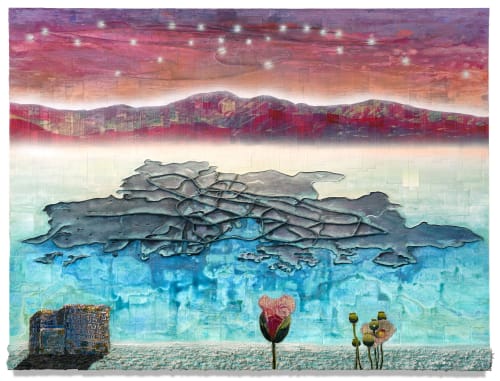

Five paintings in Tears of Paradise depict aerial perspectives of real and part prophetic landscapes, each relating to specific sites in China that collectively comprise the largest infrastructural project in human history. The sprawling cityscapes are rendered from satellite imagery, built up as reliefs on the canvas in hardened sand and pigment. The scenes’ relationship with reality is destabilized by the overall compositions, which feature floating cities below glimmering constellations that mark out future geopolitical maps, such as the “One Belt One Road” trade route.

Science fiction narrative and aesthetics have always been a cornerstone of Cheung’s practice – here they are employed to explore the intersections of old and new architecture in China’s futuristic cities, which are composed of layered expressions of history and civilisation, forming a feedback loop that continually defines identities. These worlds are overlooked by backdrops of wistful mountains, layered in sprayed acrylic paint, inspired by the dynastic classical landscape paintings hanging in the Great Hall of the People.

The works map the administration’s planned consolidation of some of the worlds’ largest cities into several inconceivably large megalopolises. In one work, the cities of Beijing, Tianjin and Hebei float like drifting islands, inviting contemplation of the future city of “Jing-Jin-Ji” – with a population of 100 million residents in an area larger than Britain. In another we see the Pearl River Delta Region, encompassing nine prefectures whose planned combination will total 120 million inhabitants. The paintings are traversed by unfathomable infrastructural endeavours – such as the building of 700 miles of high speed rail, or the 50km bridges being outlaid across the country. Cheung appropriates images of these projects from online news sources, rendering them as inkjet prints on the newspaper that forms the backdrop to the works. These sites are depicted in a state of flux – pieces in a monumental puzzle of centralised state planning designed to bolster and sustain the Chinese economic miracle.

Cheung’s paintings blend real and foreseen events to articulate the speed and complexity of change, constantly weighing human costs. Suspended in the middle of the gallery is a monumental sculptural installation, entitled Home. Made from financial newspaper and bamboo, Cheung’s window installation refers to homes in China with traditional window designs that were demolished for rapid urbanisation. The sculpture hovers between states of being, suggesting a ghost architecture that would have supported the windows. The visitor is pulled back down to ground level from the god-like, macro perspective of the paintings. The windows act as a demarcation between the march of unstoppable progress, and the framework of identity, history and culture that define the individual; in Tears of Paradise, we are left pondering the greatest paradigm shift the world has ever seen from each point of view.