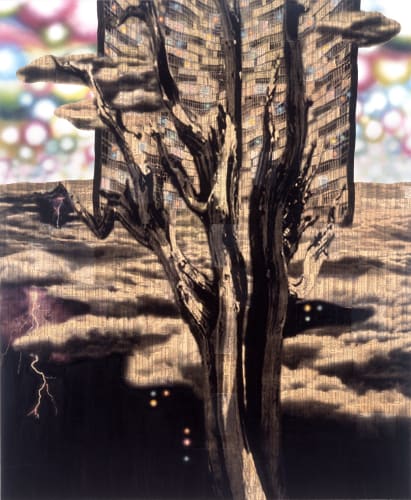

Gordon Cheung mixes decadence of apparel with a special taste of paradise. The artist plants allegories and leaves others to gather them. Using a mix of techniques he retranslates the prints of John Martin, created for the original edition of John Milton’s Paradise Lost, the departure point of this exhibition. The poem’s illustrations are revised, corrected and reproduced in technicolour, animated by his use of spray paint, ink and acrilic used like oil paint, to highlight that the disfiguration of the nature that surrounds us is so extensive that we it has projected us into an irreversible process. In a post-nucleur landspace Gordon Cheung depicts a paradoxical nature emerging from craters and psychedelic rocks, and the ruins of an indecipherable world which is almost always covered or surmounted by a cicular form like a spiritual aura whose presence serves to reassure us a little. The exhibition ‘God is on our Side’ encapsulates ideas which float in timeless incorporealty. Conceived as a triple discourse on the idea of power, the sovereignty of faith and the impotence of humanity, the works in the three rooms unmask the prevalence of money and our slavery to profit and the flux of the markets. With veiled reference to the global war on terror, the artist denounces the ease with which we invoke the divine as a justification for recent military actions. Without imposing any form of dogma, he depicts religion as mere excuse to legitimise illegal interventions. Gordon Cheung’s lastest works are of impressive dimension.

The exhibition opens with a site-specific installation of 24 works (50 x 60cm) highlighted against a single wall, portraying the various chapters of Paradise Lost. The series evokes the celebrated Miltonic poem and invites us to formulate our position vis-à-vis the rebel angels, liberally reinterpreting and simplifying themes. Milton undeniably sympathised with Satan, examining a failed ideal to try and reconcile the pagan and Christian traditions. The latter had had proved incapable of offering answers to arduous teleological questions about fate, predestination. The Trinity is negated in favour of the figures of the son and a rather sarcastic father. Cheung views the present on a metaphorical and symbolic level, which is never didactic or moralistic. Leave Eve to look in her mirror and fall in love with herself, while the pyschedelia and hallucinations of the surrounding landscape change Nature into something prismatic that assails us all as we seek to reconcile art with the real world. The artists works are founded on a series of sucessively more inaccesible places. The future is shrouded in mystery with a decisive warning about paying attention to the heart of things, the real significant fulcrum of events before confronting them and preparing ourselves. Whether positive or negative. The artists explains: “ At one point we looked towards the West and it was not only a fashion but a political formation. Today we look East without understanding that for certain things we are simply threatened by the potentail of the Chinese instead of favoured by its appealing consumerism”. The phrase ‘Paradise Lost’ has become representative of a system in progress. The title is used as simile for contemporary society, as in Mark Ravenhill’s fantastical play of the same title presented in the Edinburgh Festival, a condensed corroboration of the perils of our present in 20 minutes of choppy, staccato prose. In ‘Pandomonium’, a word first employed by Milton, Lucifer uses his powers of rhetoric to give orders, supported by his faithful lieutenants, Mammon and Beelzebub. The poem begins in media res after Lucifer and the other rebel angels have been exiled to Hell by God. After some discussion Satan decides that he will become the poisoner of the newly-founded earth. Above all, the Fall has a destabilizing effect and its repercussions are found throughout Cheung’s work; although his vision is of a world altered by mankind. Order does not exist; nor does the possibility of invoking, evoking, imagining or creating it. The artist makes reference to science fiction and evokes Ulysses and the Aeniad in the infernal regions of the Underworld. Every canvas is prepared with a background of the stock listings of the Financial Times, an English newspaper which has always been an precise point of reference about the state of the economic world and is moreover, highly esteemed and feared for the reviews on the arts in general. Having prepared the base with the best English paper, the artist covers the background with a calibrated amount of spray paint which he painstakingly prepares to produce colour tones which are commercially unavailable.. In this way he obtains the unique chromatic effect which is the hallmark of his style, using the repeated numerals of stock listings to describe and make us reflect upon the money which surrounds every transaction. The regression that society is undergoing is a conjugation of frustrated expectations and the last luxury that we can afford ourselves is to indulge in romanticisim about the destruction that we are wreaking: we empathise with the devil because we understand the nature of the conflict, the everyday struggle against hell. Eve’s desire permitted us to understand temptation and if the angels try to redeem her then they themselves must fall. This infernal council will not suceed at guiding her, and beyond there awaits a luminous landscape.

For us there remains the vision of an everyday where the sun never sets in the depths. Anything can happen, but the stars continue to shine.

Text by Raffaella Guidobono