Allegory is consistently attracted to the fragmentary, the imperfect, the incomplete— an affinity which finds its most comprehensive expression in the ruin... Here the works of man are reabsorbed into the landscape; ruins thus stand for history as an irreversible process of dissolution and decay, a progressive distancing from origin.

- Craig Owens

How do we visualize the digital? The virtual? What does the information age look like? Neologisms engendered by the invention of new technologies often tie the invisible, interstitial, or difficult to comprehend to the overtly physical: “information highway,” “cyberspace,” “surfing the net,” “downloading.” London-based artist Gordon Cheung understands that these physical associations are not mere metaphors for actions, data, or ideas that are floating around in a virtual abyss, for the information age has resulted in concrete transformations, profoundly impacting the landscapes and cityscapes that make up our physical surroundings.

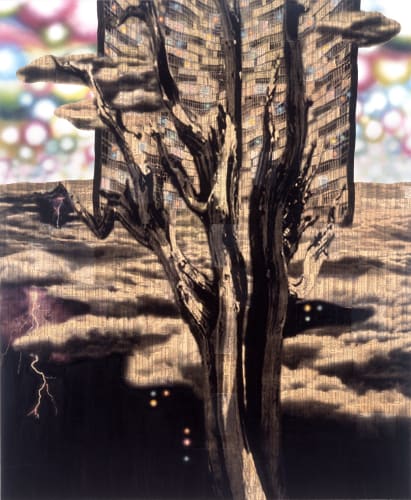

Gordon Cheung’s mixed media paintings depict sites at once generalized and idiosyncratic. Their familiarity stems from Cheung’s ability to combine numerous references into a single image, wherein space expands and contracts as if on the verge of collapse and time seems to reach toward the future while remaining firmly rooted in the past. Collaging the distinctively pink pages of London’s Financial Times onto the surface of his paintings, the columns of data serve as visual evidence of the complex digital networks that now connect countless physical locations, while also establishing a sense of cohesion in these mysterious and ominous landscapes. While several of Cheung’s paintings of 2004 position a boxy, modernist building within a natural environs (monolithic reminders of the man-made struggling against dangerous precipices or staking a claim amongst a nearly apocalyptic arid expanse), his most recent works are hallucinatory, Rorschachian landscapes more overtly rooted in the psychological and the sublime. Rendered in exquisite washy black ink with punctuations of bright, artificial colors, a bleakness permeates these sites; yet, they are tempered by a somewhat ironic, but nonetheless enchanting, optimism, often symbolized by one or more rainbows traversing the canvas.

The foreground of Cheung’s Crater (2004) is filled with craggy, steep cliffs surrounding a psychedelic lake where bursts of green, blue, and purple bubble to the surface. In some places the rock face becomes a hybrid of the natural and the hand-built in the form of walls of stacked bricks; like decaying, ancient, stepped temples, these ruins are disconcertingly warped as if viewed through a heat wave. Along the far wall of the crater, nearly indecipherable, yet somehow cheerfully familiar, graffiti covers the surface. And, in the middle of the canvas sits a Stonehenge-like configuration—an icon of the balance between and man and nature—flanked by two mirroring rainbows. The entire space is shrouded under a dark, cloudy sky with a staccato bolt of purple lightening flickering at the top edge of the canvas. It’s as if the graffiti and the ruins have been, just as Craig Owens describes in the epigram above, “reabsorbed into the landscape.” Describing his paintings as reflections of the “techno-sublime,” Cheung’s worlds derive from globalization, where images circulate widely, infiltrating and saturating even remote landscapes. The child of Chinese immigrants, Cheung has always had to negotiate between two cultures. His experience of belonging to more than one place and in more than one community and grappling with the simultaneously alienating and liberating effects of this multiplicity is becoming more and more commonplace in today’s much-traversed world. The kaleidoscopic, distorted, and reflected imagery of his paintings are both dizzyingly delightful and darkly portentous, suggesting a personal ambivalence that lies somewhere between knowing oneself and questioning one’s position in the world. Cheung’s mesmerizing sites are ultimately visual allegories presented for our contemplation, negotiating between the present and the future and encouraging a historical evaluation of today’s culture.

That Cheung chooses to work in several media and draw from a diversity of historical precedents—applying techniques as distinct as collage, Chinese and Japanese ink brush work, photographic transfer of appropriated imagery, and spray paint while referencing such art historical moments as the Hudson River School and Chinese landscape scrolls—is indicative of the work’s alignment with the postmodern embrace of heterogeneity. Remaining deliberately in the realm of painting, his willingness and comfort with quotation in both imagery and technique suggest an affinity with Rauschenberg’s combine paintings and many others thereafter who use appropriation to complicate conventional readings of images. Craig Owens notes, “Allegorical imagery is appropriated imagery; the allegorist does not invent images but confiscates them. He lays claim to the culturally significant, poses as its interpreter. And in his hands the image becomes something other...he adds another meaning to the image.” The complexity and visual impact of Cheung’s work lie, in part, in what Owens points out so eloquently about allegory: its understanding of ambiguity and ability to draw out multiple meanings, or as Owens puts it, the work, “...must remain forever suspended in its own uncertainty.” Cheung’s landscapes suggest that although our understandings of place may today be marked by amalgamation, fragmentation, and a constant state of flux, we can nonetheless visualize sites that are equal parts physical and digital, reality and perception.

Gordon Cheung received his MA in paintings from The Royal College in London in 2001 and his BA from Central Saint Martins College of Art and Design. He has been in numerous group exhibitions, including the 2004 Liverpool Biennial and “Yes, I Am a Long Way From Home” at the Nunnery in London. He recently completed a residency at the Kyoto Art Centre Residency in Japan, the VASLResidency in Pakistan, and Breathe Residency at the Chinese Arts Centre in Manchester. His solo exhibition “Hollow Sunsets” was at Houldsworth Gallery in London last year.

Text by Anne Ellegood, Associate Curator